Jogo Bonito – Beautiful Game: Guide to Playing 4-2-3-1 Like a Brazilian (Part 1)

This is meant to be Part 1 in a planned multi-part series about Jogo Bonito, Brazil’s signature style of football. It’s more of a historical origin story, tracing the winding path that Brazilian unique style of football followed over the years. It is by no means a complete history. That would take an entire book! And besides, Jonathan Wilson does it way batter in his seminal “Inverting The Pyramid”. I just wanted to set the scene and give us context before diving into more technical tactical creation in the next article(s). That will follow more typical pieces that you have seen from me in the past where I explain the roles I intend to use and the rational behind the tactic. So hopefully you enjoy this fascinating bit of football history and stick around for future content in this series.

The Beautiful Game’s Magical Pedigree: The Historical Journey From Danube to Amazon

At the beginning, there was something magical: the Wunderteam. The Austrian national team of the 1930s. Under the tutelage of Hugo Meisl, the Austrians became the pioneers of the fluid, “pass-and-move” style. A style never before seen in football. It celebrated technique and artistry over pure physical brawn and athletic running. In a break from the football of the previous era where teams would just line up their five forwards (English Pyramid) and have them dribble at the opposition in an individual show of attacking prowess, the Austrians embraced quick pass-and-move style. The Wunderteam was born. It drew inspiration from the Scottish school of football (“Combination Game”) that was all about technical prowess and quick passing. It was introduced to Central Europe by English expatriate Jimmy Hogan.

Matthias Sindelar, Josef Smistik and Walter Nausch made up the core of the team that would dominate European football during the pre-WWII era. Sindelar, known as Der Papierene (The Papery Man) because of his small, agile build, was the star and captain of the team. He was a prototypical False 9, a forward that dropped back to drag opposition defenders with him, orchestrate plays from advanced midfield strata and open up space for his teammates. The Wunderteam’s forward line was also complimented by wide half-backs and an attacking centre-half who did more than just defend.

This “Danubian School” set-up is what allowed the players’ passing skills to overshadow the individualistic dribbling, as was the case in the older Pyramid system. The fact that the central forward would drop deep, facilitated the formation of multiple passing triangles on the pitch. While The Wunderteam did not win any major international trophies, it did go on a historic 14 game winning streak. Furthermore, its beautiful brand of football inspired other teams to continue to evolve this highly-technical, teamwork-focused style. The idea that football could be more than just a sport emerged. The Beautiful Game was born.

After the Austrians, came the Magic (or “Magnificent” or “Mighty”) Magyars, the team with many names who were most definitely Hungary’s “Golden Team” of 1950s. Linked to the Austrians by their common history in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they also came to share the similar ideal for making football into a game of artistic grace and cooperation. Hungarians took Wunderteam’s modified 2-3-5 formation and changed it into a 3-2-1-4. On paper at least. In reality it was an early form of 4-2-4. A revolutionary formation that influenced two great footballing nations an ocean apart.

But going back to the Magic Magyars. The Hungarian national team of 1950s embraced the concept of the withdrawn centre-forward, ala Sindelar. Except Hidegkuti played even deeper, practically in the midfield! One could even say that the Hungarian side was perhaps the first Strikerless formation. And the Magyars went one step further by introducing the role of the sweeper-keeper. The Hungary’s manager Gusztav Sebes encouraged his keeper Grocsis to leave his traditional penalty area and “sweep-up” aggressively behind the backline. The defenders (nominally the three fullbacks at the time) were in turn given more freedom to push forward and help the two half-backs with the build-up and possession battle. At the same time one of the two halfbacks, Zakarias, would regularly drop back to aid in the defence.

Such fluid movement between positions was unprecedented at the time. Yet, it was a natural continuation of what Meisl started with the Wunderteam in the 1930s. In fact, Meisl and Sebes shared the same respect for Jimmy Hogan. But of course Sebes evolved this concept of the fluid “pass-and-move” game to a whole new level.

We played football as Jimmy Hogan taught us. When our football history is told, his name should be written in gold letters

Gusztav Sebes

In 1950s, Sebes successfully implemented Hogan’s ideal that every player should be able to play in every position. Total Football like never before. This development was critical to the success of the team. It was the exact opposite of the WM system, favoured by the English at the time. WM rigidly separated attack from defence and did not allow for the same level of movement between the lines. Each player in a team was assigned a specific position or role, usually marking a specific opposition player. In contrast, Sebes’ strategy of players constantly changing roles and positions threw the WM playbook out the window. Due to their rigid marking, the English simply could not deal with Hungary’s tactic!

Unsurprisingly, The Magnificent Magyars were quite a bit more successful than the Austrians before them. All I’m going to say on that note is that 1953 was a special year for Hungarian Football, and a dark one for the English fans of the game. Simply put, no other national side at the time could match the Hungarian juggernaut in its integrated use of attack and defence.

Although Sebes’ style of football was only possible because Hungarians were a very talented group of players, long used to playing together at both a club and national level. It would be nearly 20 years before the Dutch used the same fluid approach with their own brand of Total Football. And again it took a golden generation of footballers to bring the Total Football dream back to reality.

Though all six of us [Bozsik, Czibor, Budai, Puskás, Kocsis and Hidegkuti] could attack, we never played in a line formation. If I went forward, Puskás dropped back. If Kocsis drifted wide, Bozsik moved into middle. There was always space to play the ball into… we constantly changed positions, so where we lined up at kick-off was irrelevant.

Nandor Hidegkuti

4-2-4, the formation that became synonymous with Brazilian football, for a time, was conceived as a further development of the Hungarian WW. It combined a strong defence with an even stronger attack, and was actually the first formation to be described using numbers. The 4-2-4 formation made good use of the players’ with elite-level fitness and technique (never lacking in Brazil), aiming to effectively use six defenders and six forwards (with the two midfielders performing both tasks depending on the phase of the game, as sort of prototypical box-to-box players).

Unlike the tactic systems that came before, the 4-2-4 allowed for essentially four defenders at the same time (when out of possession). The fourth defender increased the number of defensive players and allowed them to be closer together, thus enabling effective cooperation among them. The main point being that a stronger defence would allow an even stronger attack. This fourth defender (usually the right wingback) would also be allowed more attacking freedom, dribbling up the field to provide a deep crossing threat on opposition goal. The idea for aggressive “flying” wingbacks was very much born in Brazil.

Initially, 4-2-4 shape arrived in Brazil via Hungary. It started with the tactics devised by Marton Bukovi. To link back to Hungary’s Golden Team, Bukovi played a major role in the success of that legendary Mighty Magyars team. It was Bukovi, working as a manager of MTK in Hungary, who first developed the 4-2-4 formation in order to accommodate the club’s star Nandor Hidegkuti as a revolutionary deep-lying forward/false9. Because of MTK’s and Hidegkuti’s success, the tactic was soon adopted by the national coach Gusztav Sebes. Then we already know what happened after. Hungarians dominated other European teams, including the mighty England for quite some time. And then the tactic was exported to Brazil by another Hungarian coach, Bela Guttmann.

Guttman briefly managed São Paulo and won the championship with them while using the Hungarian 4-2-4 formation. This undenibly helped to cement this formation’s popularity in Brazil. Although the credit should not solely go to Guttman. Flavio Costa, Brazilian national coach in the early 1950s, also played an important role in “perfecting” the Magyars’ tactic in South America.

Thanks to Flavio Costa, Brazilian-style 4-2-4 finally came to the international spotlight at 1958 World Cup. There the Brazilian national team, that was trained in the use of the new tactic by Costa, was crowned champions. Then they went on to be tactical revolutionaries again in 1962 World Cup in Chile where largely the same team played a slightly modified 4-2-4 to capture another Cup. Famously this formation had left winger Zagallo dropping back and going more central (due to injured Pele) to play an early version of 4-3-3, long before the Dutch made it cool. But no matter how they lined up or played, the Brazilians were always a joy to watch.

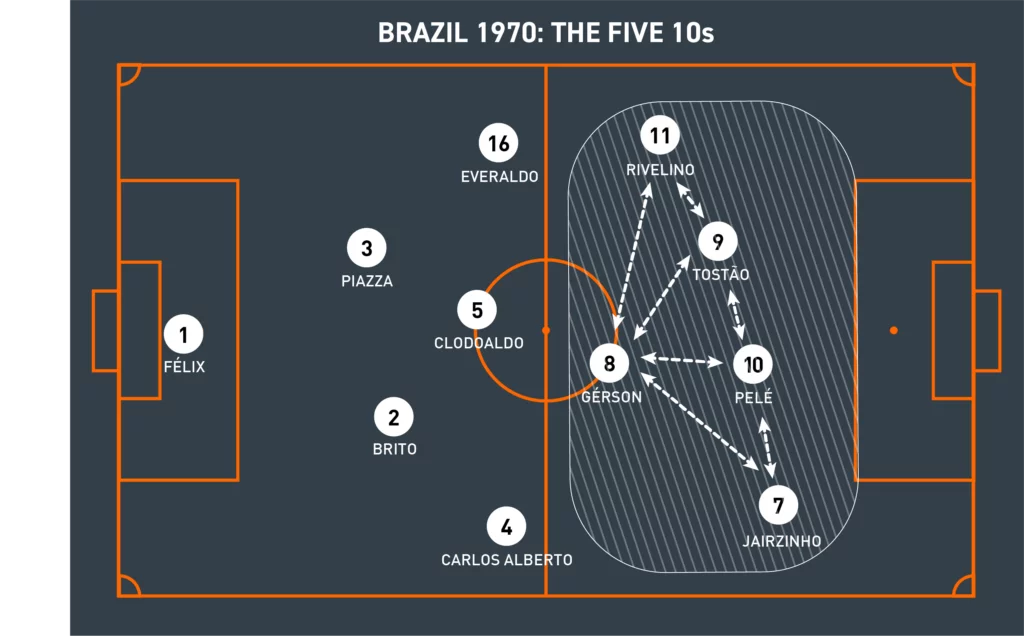

So if 4-2-4 was a natural evolution of Magnificent Magyars’ WW, then in turn Brazilian 4-2-3-1 developed from that same 4-2-4. In many aspects, the more traditionally Brazilian 4-2-2-2 “Magic Box” formation (the mainstay of Brazilian football for almost 30 years between 1982 and the early 2000s) also evolved into 4-2-3-1 over time. The 4-2-4 was famously used by the Brazilian national team at 1970 World Cup. Mario Zagallo, Brazil’s legendary left winger-turned-coach, saw his team as pioneers of the 4-2-3-1 shape. Although the 1970 national team tactic was more of a false 4-2-3-1 if anything. Meaning that on paper it was 4-2-4 but in motion it quickly transformed into 4-2-3-1. Zagallo had his left winger (Rivelino) play as a quasi-midfielder/defensive winger (just like Zagallo played himself in 1962) granting the formation its midfield numerical advantage.

This not only allowed for better ball control and progression but also a stronger defence than in a pure 4-2-4. Zagallo also set his midfield to be staggered for better vertical movement of the ball. Exactly like in a modern 4-2-3-1 with its four lines/strata of defence, central midfield, advanced midfield and attack. But of course, in typical Brazilian fashion there was a lot of fluidity, interchanging of roles and blurring of lines. It was the original Samba Football at its finest. Jogo Bonito! And this wondergoal by Carlos Alberto is the perfect testament to the artistry of that 1970 team.

In a modern 4-2-3-1, The two midfielders normally play closely together to protect the defence, and move laterally across the field as a coordinated unit. The formation is usually played without wide midfielders. The three attacking midfielders (AML, AMC and AMR) split across the field to spread the attack, like three prongs in an attacking trident, and may be expected to mark the opposition full-backs as opposed to doubling back to assist their own full-backs, as do the wide midfielders in a 4-4-2. The central striker is the advanced attacking pivot that is expected to be physically-strong and technically-adept as he controls everything in and around the opposition penalty area.

The 4-2-3-1 formation’s free attacking nature is even further emphasized in Brazilian football. The Brazilian 4-2-3-1 grew both out of the formation used by Zagallo in 1970 and the later 4-2-2-2 Magic Box. While in Europe, the 4-2-3-1 emerged out of the attempt to make 4-4-2 into a more elegant shape for both attack and possession. In Brazil it was just a reflection of how freely formations morphed from one to another. It was a natural evolution in that original WW formation that came from Hungary with Marton Bukovi and Bela Guttman. For what is 4-2-3-1 if not a wide 4-2-2-2? This was best showcased at the 2009 Confederation Cup where Brazil played in an interesting shape, that was both instantly familiar and refreshingly new.

You see, the European 4-2-3-1 derives from 4-4-2. You have your standard deep-laying central forward, the wide players that can both provide width, cut inside, and help deal with the opposition full-backs. But the Brazilian-style 4-2-3-1 draws more from the 4-2-4 (which is really a false 4-2-3-1) and its later 4-2-2-2 modification. When it was first showcased to the world in 1982, the 4-2-2-2 had Falcao and Cerezo operating as deep-lying playmaker double pivot behind the two narrow trequartistas Zico and Socrates. The four of them together made up the “Magic Square”. Unfortunately that team could not win the ultimate trophy. But what they did do was to further cement the 4-2-2-2 “Magic Box” tactic as a natural stepping stone from the earlier 4-2-4 to the more modern 4-2-3-1.

The eventual evolution towards the Wide 4-2-3-1 system came about by pulling one of the two strikers back and wide into an inside forward position. At the same time one of the two AMC playmakers moved wider to the flank. While the double pivot in midfield is preserved and the wingbacks still provide much of the formation’s width. This became most apparent at the 2009 World Cup where Brazil once again surprised the world with its tactics.

Can you see now how the Brazilian 4-2-3-1 is not quite the same as the European derivation of that shape? Football pundits love to throw formation labels around but in reality this collection of numbers is but an abstract simplification of the shape that the team is using. And educated guess at best. Or just an attempt to fit the much more complex collection of movements and strategies, performed by 11 players on the pitch, into a neat logical box. Well, sometimes not everything fits neatly, and round pegs don’t fit into square boxes. In the end, labels and numbers don’t really matter as much as visual evidence of brilliant, timeless football that is too unique to fit into any formation or style category. Brazilians always liked to play outside the box, defying European expectations and playing purely for the joy and beauty of the sport.

Now, with the historical background out of the way, it is time to get down to the nitty gritty tactical analysis. Hopefully after reading my little introduction, you might get a taste to attempt your own experiment in creating Brazilian-style tactic (whether 4-2-3-1 or other). I’m certainly excited to proceed with my own FM23 experiment. Especially after my research showed just how closely Jogo Bonito was to the legacy of Austrian Wunderteam and Hungary’s Golden Team.

So that gives me more than a few ideas on what I want to see in my eventual Jogo Bonito tactic. Fluid, pass-and-move, attacking football. Progressive possession = possession with intent. I don’t care about raw numbers and statistics but actually that my players do something game-changing every time they possess the ball. Not just possession for the sake of possession. In modern football, some might call such a style, Vertical Tiki-Taka. I just call it the football that the Austrians started, Magyars improved, and Brazilians perfected. The Beautiful Game.

So with that out of the way, I will be diving into the full tactical role analysis in Part 2, but as a little preview I will give two key roles here.

The Second Man

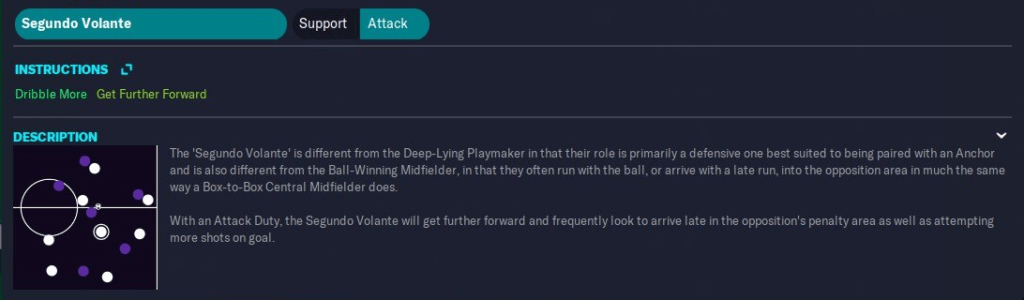

To start off the role analysis, I go to the most iconic and most “Brazilian” role in any historic Brazilian formation. The role of Segundo Volante.

Unlike the other exotic roles in FM23, it has an interesting origin story. And I think it needs to be told to fully appreciate what makes this role special. Firstly, “Volante” became a word to describe a typical hard-tackling, tough-as-nails” Ball-Winning Midfielder. Simply because Carlos Volante was such a midfielder for Flamengo during the late 1930s. He was such an archetype of this role that his name stuck around as a way to define it. Sort of like if Italians decided to rename a deep-lying playmaker (regista) “Pirlo”. I’m rather surprised it didn’t happen actually. But anyway the name stuck in Brazil. and that is where the term Segundo Volante was mostly used, until Football Manager put it into the lime-light a few years back. And as all things FM go, it has become very mainstream with virtual managers and football hipsters everywhere. But wait, what is Segundo Volante then?

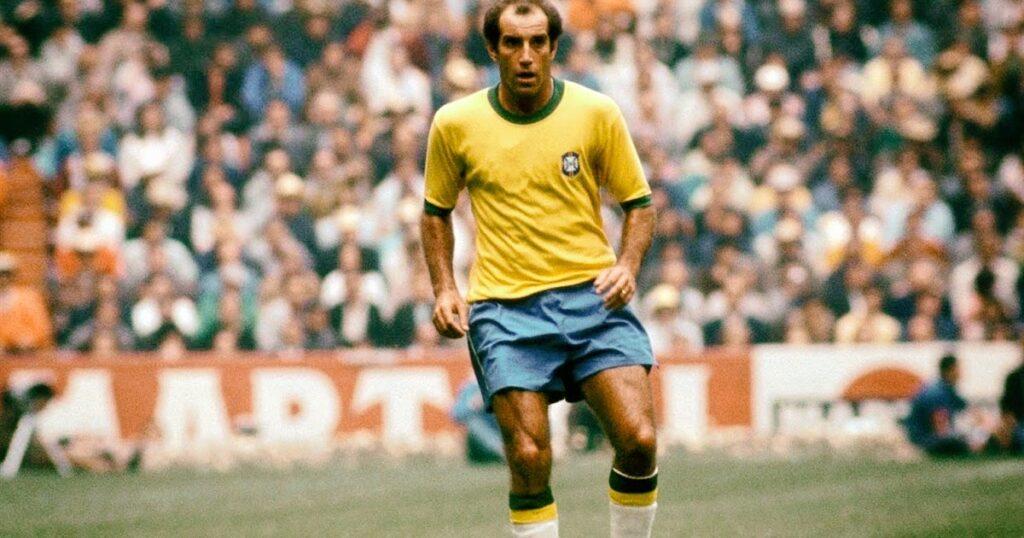

Well, in the 1970 world cup, Brazil used its famous 4-2-4 formation. Or to be a precise, a modification of 4-2-4 which played more like 4-2-3-1 than anything else. During radio broadcasts, the pundits in Rio De Janeiro would, as always, name the two deep midfielders as the Volantes. Except there emerged one important distinction. Gerson, one of the playmaking stars of the team, just refused to behave like your typical Volante. He was referred to as the Segundo Volante – Second Volante, because he behaved rather differently from his more typical Volante partner.

As the second defensive midfielder, Gerson was the key piece in Brazil’s attacking machine. He was one of few similarly creative players – “The Five #10s” as football historians tend to describe the play-making talents of Pele, Tostao, Rivellino, Jairzinho and Gerson. These five players were all essentially exemplary playmakers (albeit Pele was a well-rounded one who could both score and assist) and thus became nicknamed for the traditional #10 advanced playmaker role. But even in such an elite group, assembled by Brazil’s manager Zagallo, Gerson became the main creative influence. Firstly, as the main source of short passes to his DM partner Clodoaldo or towards the wingbacks. Secondly, his long passing range allowed him to link-up effectively with the four attackers. As one of the five 10s, Gerson also made late runs into dangerous areas where he could create chances for a teammate, or take a shot on goal himself.

Gerson was the glue that held the formation through its middle. And that is exactly what I am looking my Segundo Volante to do in the game. As his in-game description suggests, I need this player to act both as a defensive pivot to help put up the last defensive barrier before our centrebacks and as a ball-carrying playmaker/late runner to move forward and support our attackers in possession. It is a very demanding role, which can easily be seen just by the attributes needed.

So in a typical play, once Segundo Volante’s midfield partner (more defence-focused DM or perhaps Anchorman) wins the ball back, he passes short to our Segundo. SV has a few options such as passing it to the closest teammates like the wingbacks. Or he can decide to drive forward with the ball to more dangerous area from which he can feed any of the front four attackers. With a suitable player in the Segundo Volante role it quickly becomes apparent just how important this player can be to the whole tactic. As part of the double pivot in central midfield it is the role around which the rest of the formation can rotate.

The Luxury Player Role

Complete Attacking Wingback (CWB) – another uniquely Brazilian role. In truth, it was Brazilians that invented the modern wingback and it is a role that thrives in Jogo Bonito-style football. The player whom you saw scoring that wondergoal a few paragraphs back was in fact a wingback. Carlos Alberto Torres – The one and only. The star player of 1970 World Cup. He was one in the long line-up of stereotypical Brazilian wingbacks. Powerful, lethal, fast, unpredictable, exceptionally athletic and tireless. Other notable examples being Cafu and Dani Alves. All Brazilians of course.

Players like Carlos Alberto possessed the pace, stamina, and the technical skill to do overlapping attacking runs, perfectly blending the roles of a fullback, midfielder, winger, and even striker at times. Much like a deep-lying winger, Brazilian wingback is expected to be an accurate crosser of the ball, an essential link-up player between defence and attack. In addition to chance creation, a CWB has to provide and effective threat on goal, to reflect the “winger” portion of his name. And Carlos Alberto was definitely known for his ability to score game-changing goals. He is another look at that amazing goal. I could watch all day. Is Italian keeper trying to swim through the grass? Or just wishing the ground opens up and swallows him up?

Brazilian wingbacks were far from the original fullback role, more wide attackers than defenders. Although, Carlos Alberto was a very well-rounded player who did not neglect his defensive duties. It was just not that much required of him because of the kinds of teams he played for. In this sense, a Complete Wingback is true “luxury player”. It takes a pretty good team to be able to tactically afford to play a 3rd wide attacker in a deeper position.

However, if you decide to fit CWB role into your tactic then it usually means that your team is already set up in a way to provide the necessary cover for the wingback to get forward and do what he does best. As a result, teams with a very attacking wingback usually line up with a more defence-minded fullback (or wingback with defend duty) on the opposite flank. And perhaps one central midfielder in a deeper position or with a more cautious role on the same side as the attacking wingback.

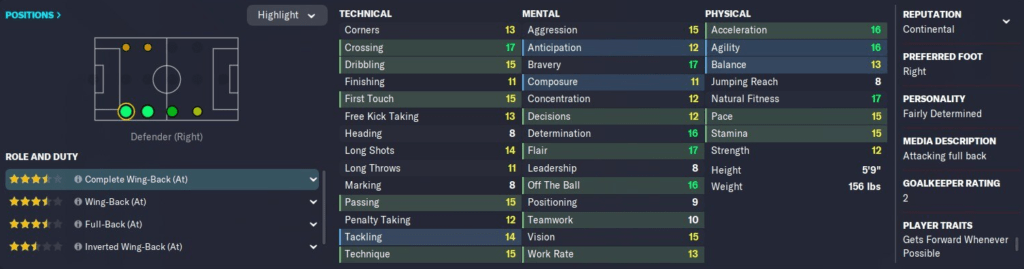

Also, very few teams at the start of the game possess a player who is natural or accomplished in the fullback or wingback position and also fitting the attribute profile of a Complete Wingback.

On the other hand, many teams already have a physically fit, hard-working and relatively technical winger. Even if his Tackling or Positioning is not up to par, I see no problem playing such player in the deeper position to take advantage of his more attack-oriented attributes in the fullback strata. As a wingback he can be very dangerous, even if he is only an average AMR/AML strata player. Besides when you decided to use CBW role it is not for his defensive/covering capabilities, you will already have other players doing that in your tactic.

To be continued …

Other Articles You May Enjoy

If you enjoyed this, then make sure to follow us on Twitter and Facebook to keep up with all Dictate The Game content. Thank you for reading!

3 thoughts on “Jogo Bonito – Beautiful Game: Guide to Playing 4-2-3-1 Like a Brazilian (Part 1)”

I love the 4-2-2-2 system from the brazil side in 82, would love to get more media about it, love this article.

Something like this maybe?

http://dictatethegame.com/young-devils-samba-united-and-the-magic-box/

I wrote it for an older FM but I figure the tactical principles would still be the same. I might do an update sometime in future 😉